Books & Prose

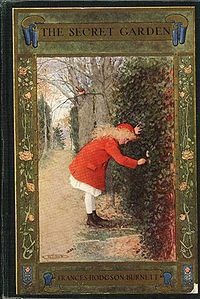

Review: The Secret Garden, Frances Hodgson Burnett

By Anna M. Warrock

There comes a moment in every childhood when we become certain the family we live with is not really our family. These strange people do not understand us. We belong elsewhere, we decide with a sad, determined fierceness. Thus begins the process of making a home within ourselves.

For many reading this, that home within finds expression in what a dirt and chlorophyll garden embodies: the magic of the soil, air, and water that forms a rose; a wonder at the myriad of forms creation takes; a willingness to work for beauty; and a small door that opens into the unknown, leading to the surprises a garden brings to life. For us, there is the Bible, Diamond Sutra, Koran, Torah, or Descartes – and Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden, first published in 1911.

Young Mary, sent to her reclusive uncle’s Yorkshire manor house, has lost parents she hardly knew. On that train to the cold and rainy country (akin to a New England February), the angry, self-absorbed girl doesn’t seem to have much future. Burnett gives her a ray of hope. The first morning a talkative servant tells Mary, who must play by herself outside, of a locked, walled garden she won’t be able to enter. Outside Mary searches, “There were trees, and flowerbeds… but the flowerbeds were bare and wintry, and the fountain was not playing. This was not the garden which was shut up. How could a garden be shut up? You could always walk into a garden.”

Young Mary, sent to her reclusive uncle’s Yorkshire manor house, has lost parents she hardly knew. On that train to the cold and rainy country (akin to a New England February), the angry, self-absorbed girl doesn’t seem to have much future. Burnett gives her a ray of hope. The first morning a talkative servant tells Mary, who must play by herself outside, of a locked, walled garden she won’t be able to enter. Outside Mary searches, “There were trees, and flowerbeds… but the flowerbeds were bare and wintry, and the fountain was not playing. This was not the garden which was shut up. How could a garden be shut up? You could always walk into a garden.”

From that moment, we know that the girl’s hope grows in that garden. The gardener, Ben Weatherstaff, as solitary and “nasty-tempered” as the long-isolated Mary, becomes her first friend, after hearing Mary tell his half-tame robin that she’s lonely (her first self-knowledge, different from self-absorption). Then Mary hears of Dicken, the nature boy who knows and is known by the blackberries and the foxes, and she longs to meet him for the magic he knows of the wider world she begins to embrace.

Mary discovers the secret garden on her own. The garden is, of course, the garden we have all locked ourselves out of. A robin helps her find the key. Once inside, she instinctively begins clearing the grasses from around the green points of crocus and daffodils poking up. Not a miraculous reunion with her parents, which could not be, the garden of the uncle’s lost love, the adult loss through tragedy, is resurrected by the children’s caring, just as the uncle has provided a haven where Mary can heal.

Burnett emphasizes the mythic nature to this homely story as she lets Mary claim the Secret Garden. “It seemed almost like being shut out of the world in some fairy place,” she thinks as she plays there, remembering the fairy tales with secret gardens. “Sometimes people went to sleep in them for a hundred years, which she had thought must be rather stupid. She had no intention of going to sleep, and in fact, she was becoming wider awake every day which passed at Misselthwaite.”

She uncovers the gray manor’s saddest secret, the sickly Colin, and brings him to the garden. With the help of the Yorkshire house staff, the old gardener and the nature boy, she learns about resurrecting the abandoned and isolated, and in the process, growing beyond her orphaned self.

I cannot read this book even decades after the first time without feeling the sadness and the joy. Through struggle and sorrow, the garden has never abandoned anyone. Burnett says it waits there behind the wall for us to discover, to find ourselves in, and to prune and dig to help the roses blossom.

© Anna M. Warrock

Originally published in the Somerville Garden Club newsletter, 2003.